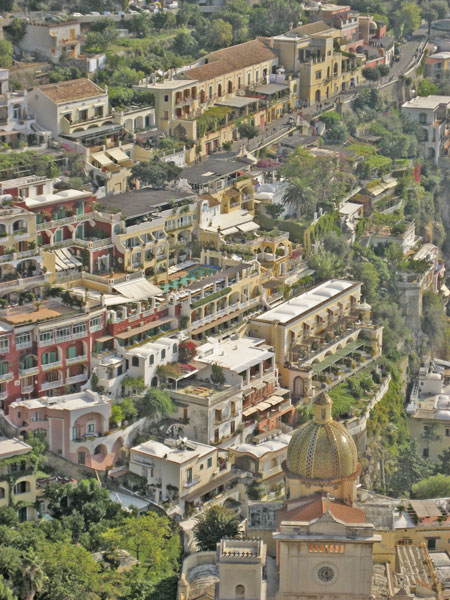

Back in October, I told you I was making Limoncello, a traditional drink of Italy’s Amalfi coastal area, but adapting the recipe. The traditional recipe calls for soaking lemon peel in 100% proof alcohol and after a period of time, adding a syrup of sugar and water. I find the real thing sickly sweet and so I squeezed the lemons I’d peeled and reserved the juice for the syrup. The resulting liquore isn’t clear, like traditional Limoncello because the juice makes it cloudy, but the taste is so much better.

Limoncello alla Passante

1 pound of lemons

2 cups of 100 proof alcohol (or you can use vodka as I did)

1 cup of sugar

2 cups of lemon juice

Peel the lemons thinly—there should be little or no pith. Steep the peelings in the alcohol at room temperature for 30 days. The alcohol will take on the flavor and color of the lemons. At the end of the steeping period, strain the alcohol into another bottle. Make a syrup from the sugar and strained lemon juice. Add to the alcohol. Store in the fridge for at least 30 days. The longer it’s kept, the mellower it will be.

Serve chilled but not over ice in small liqueur glasses (it’s very potent) after a meal as a digestivo.

Salute!

Posted by Judith

Posted by Judith