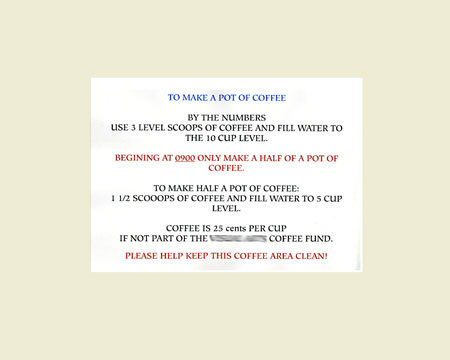

As I said the day before yesterday, I strive to be flexible on changing usage as our language evolves, but I won’t be flexible when sloppy writing or proofreading creates a document with anomalies that can’t, however flexible one is, be called anything but mistakes and/or have the potential to obscure meaning. Take the sign posted over the coffee machine in my department at the Defense Acquisition University, FOrt Belvoir, Va.:

As I said the day before yesterday, I strive to be flexible on changing usage as our language evolves, but I won’t be flexible when sloppy writing or proofreading creates a document with anomalies that can’t, however flexible one is, be called anything but mistakes and/or have the potential to obscure meaning. Take the sign posted over the coffee machine in my department at the Defense Acquisition University, FOrt Belvoir, Va.:

TO MAKE A POT OF COFFEE

BY THE NUMBERS

USE 3 LEVEL SCOOPS OF COFFEE AND FILL WATER TO

THE 10 CUP LEVEL.

BEGINING AT 0900 ONLY MAKE A HALF OF A POT OF COFFEE.

TO MAKE HALF A POT OF COFFEE:

1 1/2 SCOOOPS OF COFFEE AND FILL WATER TO 5 CUP LEVEL.

Let’s take a look at the easy stuff first. There’s an “n” missing in “beginning,” and the second instance of “scoop” has acquired an extra “o.” Maybe a scooop is bigger than a scoop, but I tend to doubt it. Someone made this sign in a word-processing program. How difficult would it have been to run the spell check?

Moving on:

Fill water to 10 cup level. Let’s not be persnickety about the missing hyphen in “10-cup” and go straight to the more important issue: How do I fill the water? I thought I’d need to fill the pot.

Begining at 0900 only make half a pot. Does this really mean I can make half a pot and do nothing else with it? I can’t smell it or drink it or pour it down the sink at the end of the day?

Poor old “only” is one of the displaced (pun intended) persons of the adverbial world. When I was teaching English 101, I used to give the following sentence to students and ask them what it really meant. It was almost always (U.S. high school English teachers, are you listening?) the speakers of English as a second language who got it right.

I only saw roses in the garden.

“The only flowers you saw were roses,” was the usual answer.

Bzzzz! Wrong! What it means (but you know this) is either that I saw the roses and that was my only interaction with them — I didn’t smell them, eat them, pick them, or dig them up — or that I and no other living being saw the roses.

I’d explain that if they wanted to indicate that they’d seen roses and nothing else (no daisies, wallflowers, lawn mowers, or garden gnomes) they needed to write the sentence this way: I saw only roses in the garden.

Then I’d ask my students how many different meanings they could get out of that sentence by moving just the adverb, and if the same position of the peripatetic word could make the sentence mean more than one thing, or if the same position of the adverb could make the sentence mean different things. The majority of them struggled with the exercise, and some of them didn’t grasp (even after explanation) that where you put the adverb really does change the meaning.

I saw roses only in the garden. Two possibilities: the roses were in the garden and nowhere outside it, or the only things in the garden were roses. It depends on whether you stress the words “only” and “garden,” or insert an almost imperceptible pause after “only.”

I saw roses in the garden only. Also means they weren’t anywhere else and is a construction you might use, putting a bit more emphasis on “garden” or “only” to distance yourself from the delusional person who said there were roses growing in the middle of the fast lane on the interstate.

Back to sloppy instructions. Here’s a sign that’s at the front of my local cheap restaurant: Please wait for the hostess to be seated. Hey, I’m the customer, so why do I have to wait for her to sit down?

I have treasured this one for more than 20 years. It hails from the United Kingdom and is (or was—let’s hope someone eventually caught it) the instruction on a stick of solid deodorant: Remove cap and push up bottom.

Let’s return to Fort Belvoir. Every so often, the Army conducts training near my building for the dogs that sniff for explosives, posting a sign that I assume is intended to tell people not to interfere by walking through the area — but maybe it really is warning us against the Army’s latest weapon: beagles that go bang and dobermans that detonate.

DANGER

EXPLOSIVE DOG

TRAINING IN

PROGRESS

Posted by Judith

Posted by Judith

I’m managing editor of a magazine. In the real world, that would mean I’d sit in a corner office and watch my underlings edit copy. In the world of the U.S. government (and especially as a contractor), I sit in a cubicle—okay, it’s decent-sized and has two windows—have no underlings, and do most of the copy editing myself. As I blue-pencil manuscripts, I try not to be a hidebound

I’m managing editor of a magazine. In the real world, that would mean I’d sit in a corner office and watch my underlings edit copy. In the world of the U.S. government (and especially as a contractor), I sit in a cubicle—okay, it’s decent-sized and has two windows—have no underlings, and do most of the copy editing myself. As I blue-pencil manuscripts, I try not to be a hidebound